DynV's Profile - Community Messages |

| » DynV replied on Tue Nov 13, 2012 @ 10:03pm. Posted in A Message in the Public Interest. |

Chamillionaire - Internet Nerds Argue | |

| » DynV replied on Mon Nov 5, 2012 @ 8:00pm. Posted in The NEW My Dream Thread. |

I was a middle-class asshole with a boat. the river intertwined with a sparsely populated road. I was navigating thoughtlessly ; I even went on the road with my boat a few times. my last thought before waking up was a pop song. something cheesy with "baby" here and there. I'm afraid a pop-song composer lies dormant in me. yikes! Update » DynV wrote on Wed Nov 7, 2012 @ 7:42pm non-existing pop song (which I made up) | |

| » DynV replied on Mon Nov 5, 2012 @ 1:54pm. Posted in Post Events!. |

Kuzutetsu j'suis certain qu'y en a beaucoup plus qu'on s'en aperçois. j'faisais référence aux forums. | |

| » DynV replied on Sun Nov 4, 2012 @ 6:24am. Posted in Selling my racing rig :(. |

t'as sauté ma question. | |

| » DynV replied on Sun Nov 4, 2012 @ 2:47am. Posted in Post Events!. |

at least the site is spam-free. | |

| » DynV replied on Sun Nov 4, 2012 @ 2:43am. Posted in Selling my racing rig :(. |

y'a de la force de réaction au siège? fais-toi pas d'idée, même si tu me donnais je le prendrais pas (je vends pas les cadeaux). | |

| » DynV replied on Sun Oct 21, 2012 @ 11:17pm. Posted in your video of the day. |

skip to 1:42 and listen carefully Another Pakistani girl faces Taliban threat | |

| » DynV replied on Sun Oct 21, 2012 @ 7:06pm. Posted in Chicha/Hookah. |

| » DynV replied on Fri Oct 19, 2012 @ 12:34am. Posted in Busted by STM. |

Originally Posted By DACAV I asked them if they have the right to detain or if i am free to go but he told me that he has the power to arrest me. not identifying oneself, within the limited required information, when caught breaking a by-law is an arrestable offense. Originally Posted By DACAV They told me that i can go fight their decision in court but it will cost something if i loose. Is that true? 75$ IIRC ; the loosing party pay. | |

| » DynV replied on Tue Oct 9, 2012 @ 9:00pm. Posted in Run For Your Lives Zombie 5K -Montreal 2013?. |

Originally Posted By TREY I believe this behaviour is due to lack of volunteers at the event, thus no referees at the end. is it announced as contact or not? | |

| » DynV replied on Fri Oct 5, 2012 @ 9:51am. Posted in Party This Friday Not to Miss.... :). |

pas de prix... c'est 35$ à la porte? | |

| » DynV replied on Mon Oct 1, 2012 @ 6:28pm. Posted in What are you listening to right now?. |

Neophyte Vs. The Stunned Guys - Revolution 909 | |

| » DynV replied on Mon Oct 1, 2012 @ 3:09pm. Posted in Gangnam style...WTF?!. |

Violent 'Gangnam Style' Dance-Off | |

| » DynV replied on Sat Sep 29, 2012 @ 4:30pm. Posted in Gangnam style...WTF?!. |

I don't like the music but the video is fun. | |

| » DynV replied on Tue Sep 25, 2012 @ 9:00am. Posted in top toys of the 20th century. |

Originally Posted By NATHAN Do you mean the "Choose Your Own Adventure" books?? no it was for an even younger audience, it just had images, usually funny & weird. you followed things from room to room, maybe a serpent, mouse or something was between rooms which entice the audience to follow to the other place on the side-by-side pages image. | |

| » DynV replied on Sun Sep 23, 2012 @ 12:11am. Posted in top toys of the 20th century. |

I really really can't trace this back but I remember having a blast although I was likely under 10. it was a book with a large image taking 2 side-to-side pages having a scenery and characters where you'd follow things, usually quirky, to the next and you'd get around most of the scene ; like a haunted house. I think I'd buy 1 right away if I knew the name and it hadn't become super expensive with the rarity factor. | |

| » DynV replied on Thu Sep 20, 2012 @ 3:06pm. Posted in words you can't help but laugh at. |

Originally Posted By DATABOY awingna han +1 ça veut dire fourrer hunh? j'ai jamais compris | |

| » DynV replied on Thu Sep 20, 2012 @ 3:04pm. Posted in top toys of the 20th century. |

I've done the Construx on the right, they were fun. It's a nice trip in memory lane, but as I didn't have female friends in my tender years, I'd be interested in what girls liked. | |

| » DynV replied on Wed Sep 19, 2012 @ 4:41am. Posted in top toys of the 20th century. |

| » DynV replied on Sun Sep 16, 2012 @ 3:48am. Posted in your video of the day. |

Orbital | Are We Here | Official Video Update » DynV wrote on Tue Sep 25, 2012 @ 9:02am ORBITAL. forever. live from glastonbury 1994 | |

| » DynV replied on Sun Sep 16, 2012 @ 3:26am. Posted in top toys of the 20th century. |

I remember the mini View-Master on some Micro-Machines. I loved Micro-Machines so much! | |

| » DynV replied on Sat Sep 15, 2012 @ 10:33pm. Posted in Board Cleanup. |

I really doubt it would go so far but here's an idea. [ www.kickstarter.com ] What is Kickstarter? Kickstarter is a new way to fund creative projects. We believe that: • A good idea, communicated well, can spread fast and wide. • A large group of people can be a tremendous source of money and encouragement. Kickstarter is powered by a unique all-or-nothing funding method where projects must be fully-funded or no money changes hands. make clear specifications, say [ validator.w3.org ] critical & severe , then pester Nuclear for a number for creating the project then put your money where your digits are. one can make a poster, money jar and cut slips (featuring a shortened URL?) to bring at events. current validation [ www.rave.ca ] Result0% 0% Failures per severity critical 4 severe 5 medium 1 low 5 Failures per category Rely on Web standards 3 Stay away from known hazards 5 Check graphics and colors 3 Keep it small 2 Use the network sparingly 1 HTTP errors 1 Top Page Size1.3MB Network usage147 requests Detailed report Sev.currently sorted by descending orderCat.DescriptionBest Practice criticalUse the network sparingly There are more than 20 embedded external resources EXTERNAL RESOURCES criticalKeep it small The size of the document's markup (173.5KB) exceeds 10 kilobytes PAGE SIZE LIMIT criticalKeep it small The total size of the page (1.3MB) exceeds 20 kilobytes (Primary document: 173.5KB, Images: 1.1MB, Style sheets: 0, Redirects: 0) PAGE SIZE LIMIT criticalStay away from known hazards An input element with type attribute set to "image" is present IMAGE MAPS severeHTTP errors Invalid HTTP response received (network-level error, DNS resolution error, or non-HTTP response) severeStay away from known hazards A pop-up was detected POP UPS severeStay away from known hazards Table contains less than two tr elements TABLES LAYOUT severeStay away from known hazards Table contains less than two td elements TABLES LAYOUT severeStay away from known hazards There are nested tables TABLES NESTED mediumCheck graphics and colors The height or width specified is less than the corresponding dimension of the image IMAGES RESIZING lowCheck graphics and colors A length property uses an absolute unit MEASURES lowRely on Web standards The root html element does not declare its namespace VALID MARKUP lowRely on Web standards The document does not validate against XHTML Basic 1.1 or MP 1.2. VALID MARKUP lowRely on Web standards The embedded image or object is not of type image/gif or image/jpeg (image/png) CONTENT FORMAT SUPPORT lowCheck graphics and colors The alt attribute is missing NON-TEXT ALTERNATIVES warningBe cautious of device limitations An element uses an event attribute OBJECTS OR SCRIPT warningBe cautious of device limitations The CSS style sheet contains rules referencing the position, display or float properties STYLE SHEETS SUPPORT warningHTTP errors HTTP status code 3xx (Redirection) received and the HTTP Location header targets a relative URI warningHTTP errors HTTP status code 404 (Not Found) or 5xx (Server Error) received for a linked resource warningUse the network sparingly "Cache-Control" HTTP header is present and contains value "no-cache", or contains value "max-age=0" CACHING warningUse the network sparingly The "Expires" header contains a date in the past CACHING warningRely on Web standards The document uses an XHTML doctype that is not a well-known mobile-friendly doctype (-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN [ www.w3.org ] CONTENT FORMAT SUPPORT warningRely on Web standards The documents uses one of b, big, i, small, sub, sup or tt elements STYLE SHEETS USE warningRely on Web standards The style attribute is used STYLE SHEETS USE informationalBe cautious of device limitations The document uses scripting OBJECTS OR SCRIPT informationalBe cautious of device limitations A Table element exists TABLES ALTERNATIVES informationalOptimize navigation The linked resource format may not be appropriate for mobile devices LINK TARGET FORMAT informationalOptimize navigation The linked resource character encoding may not be appropriate for mobile devices LINK TARGET FORMAT informationalRely on Web standards The document is not served as "application/xhtml+xml" CONTENT FORMAT SUPPORT informationalRely on Web standards The CSS Style contains at-rules, properties, or values that may not be supported STYLE SHEETS USE informationalHelp and guide user input Consider adding an inputmode attribute to this input element. DEFAULT INPUT MODE I'd donate a big 0 because, as facebook, I don't give a shit about cel phones. | |

| » DynV replied on Wed Sep 12, 2012 @ 4:21pm. Posted in Ravee.ca 15 year anniversary party?. |

| » DynV replied on Sun Sep 9, 2012 @ 5:40pm. Posted in Board Cleanup. |

continuing like this would have sucked but much less than if spam weren't filtered. | |

| » DynV replied on Sun Sep 9, 2012 @ 4:16pm. Posted in Board Cleanup. |

ALL HAIL the benevolent dictator! Update » DynV wrote on Sun Sep 9, 2012 @ 4:20pm theres no "like" button for the thread :( top-right beside rating, there's a drop-down ; reds are -1 greens are +1. bliss PMs | |

| » DynV replied on Fri Sep 7, 2012 @ 12:40pm. Posted in re: Dj Bliss Blaming Mike Nter (rest In Peace) For Recent Trolling Eve. |

dispicable! | |

| » DynV replied on Wed Sep 5, 2012 @ 11:44pm. Posted in Assasination attempt on Pauline Marois. |

Originally Posted By TOY_POLICE I WILL pick a fight with anyone who derails this thread. I'm pissed. si j'écris une niaiserie icit, tu va me crisser une claque sur la geule? | |

| » DynV replied on Wed Sep 5, 2012 @ 12:38pm. Posted in Sup any oiled up dudes wanna party with a Successful Breaks DJ?. |

wendall agree | |

| » DynV replied on Sat Sep 1, 2012 @ 1:33am. Posted in Israël secoué par le lynchage d'un Palestinien à Jérusalem. |

[ therealnews.com ] State Dep't Defines Israeli Settler Violence as Terrorism US State Dep't defines settler violence as terrorism while two violent attacks on Palestinians drive Israeli coverage last week d'après moi c'est des larmes de crocodile et la seule raison qu'il font ce coup de théâtre est que les états-unis commence à perdre patience. | |

| » DynV replied on Fri Aug 31, 2012 @ 2:51am. Posted in What's your best Pc game?. |

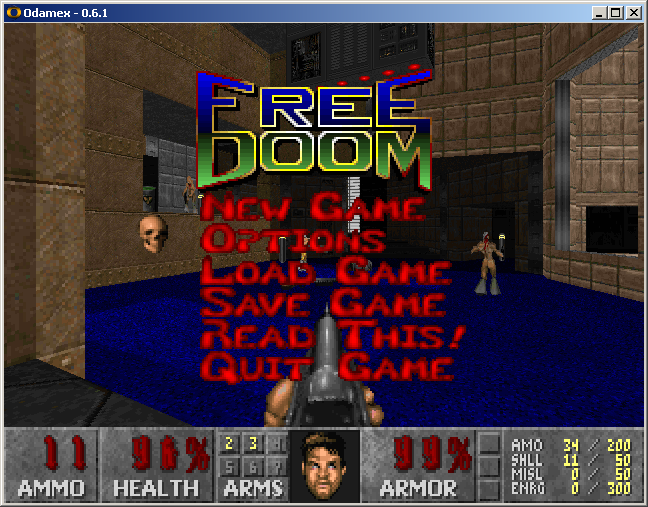

Originally Posted By PARTY_GIRL DOOM....like back in the day, :) one can play it entirely free, not just the engine, but maps & textures. [ www.nongnu.org ]  | |

| » DynV replied on Wed Aug 29, 2012 @ 12:12am. Posted in Is Full Employment Possible In Capitalism? (2/2). |

start with part 1 [ therealnews.com ] August 22, 2012 Did Obama Stimulus Work? Bob Pollin Pt5: The stimulus plan saved many jobs and helped prevent a deeper crash, but was far short of spurring a recovery PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I'm Paul Jay in Baltimore. We're continuing our discussion about Bob Pollin's new book, Back to Full Employment. And now joining us again from Amherst, Massachusetts, is Bob Pollin, where he is the cofounder and codirector of the PERI institute. Thanks for joining us, Bob. ROBERT POLLIN, CODIRECTOR, POLITICAL ECONOMY RESEARCH INSTITUTE: Thank you very much, Paul, for having me. JAY: So, once again, watch the other parts of the interview, 'cause you really should get the unfolding of the logic here. But we're just going to pick up from where we left off. So we're talking now about what are solutions, especially to the pressures of globalization. And in the last segment we talked how significant it is that employers in the United States and Canada, and Europe to a large extent, can threaten workers with these pools of cheap labor and millions and millions of unemployed people all over the world, but many of whom can now produce at a very advanced level. And that pressure has led to stagnation of wages in the United States and Canada, and Europe, I believe, and in spite of higher productivity. And now we're going to talk about, well, then, what do you do about this. This is quite objective, this ability of capitalists to do this. We discounted in the last part the effectiveness of trade protectionism and lowering U.S. currency rates. And now we're going to talk about, well, then, what can we do. And then you get to, well, first of all, stimulate the U.S. economy. And the big attempt at doing that was President Obama's stimulus program. So, Bob, take us through that program, because the critique is it didn't really work. POLLIN: The 2009 Obama administration stimulus program, the so-called American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, was an $800 billion government program over two years to inject spending into the economy. There are lots of debates as to whether the program was too big, too small. The point is that in absolute dollars it was huge. It was bigger than any stimulus program we've had, certainly since World War II, in absolute dollars. That doesn't mean it was big enough, because the magnitude of the crisis was also massive, also unprecedented. So if you measure this $800 billion, $400 billion over two years, relative to the magnitude of the crisis, it turns out that it wasn't big enough. It did accomplish things. It did counteract the decline of the private economy due to the Wall Street collapse. But it was not enough to revive the economy back onto a path even close to full employment. Let me just give two examples as to why that was true. One of the factors in the collapse, the Wall Street collapse, was the decline of household wealth. So you actually had household wealth between 2008 and 2009 decline by about $17 trillion—$17 trillion. That's more than 10 percent of U.S. GDP. So it was about—$70 trillion was the total level of household wealth before the crisis, and then after the crisis it's down to $53 trillion. Now, when people experience that much decline in their wealth, the decline in the value of their homes, largely, the value of their other assets, whatever stocks, bonds, pension funds they're holding, then they spend less. And if we follow some of the economic research on this, what we would expect with that level of a collapse is that you would reduce household spending by about $500 billion right there. So more than half of the money that the stimulus is kind of injecting into the economy is getting withdrawn at the same time due to the collapse of household wealth. So that's one reason why the stimulus was too small. Another was: while the federal government was injecting this $800 billion over two years into the economy, state and local governments were facing a huge collapse of their finances. So the money was—some money was going to state and local governments to keep them propped up in terms of their spending, but that was only partially compensating for the loss of funds that the states had. For example, our own institution here, UMass Amherst, I was on the budget committee of UMass Amherst, and we faced a huge crisis and the prospects of major layoffs. We got a stimulus check of $50 million. That meant that we could stop the layoffs, but it didn't mean we could add more jobs. So the stimulus program again was just covering in part the hole that was created by the state and local government financial crisis there. So for those reasons and a few others similar to that, the stimulus was not enough to compensate for this massive Wall Street collapse. JAY: So I think then some people would argue or ask the question: then why wasn't it made bigger? And some people have argued, actually, if you actually take the size of what was getting out of the economy, it should have been at least even double in size. But is perhaps one of the reasons it wasn't bigger is because if you take out this Keynesian toolkit, the banking and business elite, they understand at times when the economy's about to melt down you can take out some of these Keynesian tools, you can have a certain amount of stimulus, but they don't want enough to actually do what you're hoping it would do, which would actually significantly change employment rates, because that would shift sort of a balance of power back to workers, they would start to gain some leverage, wages would start to go up, so, you know, those who now have, you know, control of public policy at the federal level and state level, majority, they'll only do this stimulus just enough to stop a meltdown, and then they go right back to, okay, relatively high unemployment ain't so bad for us? POLLIN: I think you may be giving them a little too much credit in terms of their ability to know how big the stimulus should have been. I don't doubt your overall perspective. I don't doubt that there are a lot of people, politicians, certainly virtually all Republicans and a high portion of Democrats, that do not want a high-pressure, high-employment economy through which workers have growing bargaining power. I don't disagree with you on that at all. On the issue of how big the stimulus needed to be at the moment, it was actually hard to know it. And I confess I myself underestimated the magnitude of how big the stimulus should be. I mean, I wrote an article in The Nation right after Obama got elected, and I sketched out a level for the stimulus which wasn't all that different than the one that got enacted, and I didn't have the motives that you are—. JAY: Yeah, Bob, I understand that, but within the first two years of the administration, when the Democrats still controlled both houses, a year, a year and a half in, one then could have said, okay, it wasn't big enough, there should be another one, and you and a lot of others were saying that, but we sure didn't get that. POLLIN: Sure. The other part of the story, which is also in my book, is the other side, which is monetary policy, the role of the Federal Reserve in mobilizing the credit system. And here we also have this massive blockade, which you and I have talked about many times but deserves to be talked about—especially, the Fed is meeting just today to talk about some new policy measures they might pursue. The point is that monetary policy looks like it's highly, highly, highly stimulative, 'cause they've dropped the interest rate that banks have to pay to get money, to get liquidity down to zero percent. They get money for free. But that is not working in terms of stimulating activity in the economy, because the banks take the money and are sitting on it and are hoarding it. So they're now sitting on $1.6 trillion—again, 10 percent of GDP. So the idea that we have a stimulative monetary policy is not true inasmuch as the money is not getting out into the economy. JAY: And just—we've talked about this before, but let's do this again, too. And it's not that they're just sitting on it, too. They're also making money out of it (they're just not loaning it into the productive economy) in terms of carry trades, where they, you know, pick up money on foreign currency exchanges, or even still derivatives plays. POLLIN: Well, yes, they're doing all of those things, Paul. But I'm even talking about an even simpler thing. They're holding this money in cash accounts at the Fed, $1.6 trillion. They're also doing the things that—the other things that you're talking about, speculating in derivatives, in carry trade. They are doing those things. The only thing they're not doing is lending money to small businesses to get them going, so that if we don't have a government stimulus, a public-sector spending stimulus to, for example, keep public schools growing, to hire teachers, to hire bus drivers, to hire cafeteria workers, for example, to hire firefighters, if we don't have that coming and at the same time we don't have money coming through the private credit system to the small businesses, that's why the economy's stuck. JAY: And does there not also be, if there's going to be this kind of stimulus instrument used, that it's targeted and it's big enough to really have an effect on workers' ability to demand higher wages? Otherwise, don't you just have a period of time where the stimulus has an effect and then it starts to peter out, but you're right back to the same situation, which is there isn't enough real demand in the economy and you're back into paralysis again? POLLIN: That is exactly why I try to stress so much full employment as the goal and also say full employment is not just about a statistic with the number of people who have jobs. Pushing the unemployment rate down, say, in the range of below 4 percent, will empower workers. And, yes, capitalists will resist it. But it will also bring demand into the economy, and that, businesses are going to find, is going to be good. They're going to find that people have more money to spend. And that will allow them to invest more and expand their businesses. And that's exactly why the small businesses in particular would benefit tremendously by a successful stimulus program. JAY: And, again, that's if you had a political regime, a government that actually had as an objective full employment, 'cause right now these guys are actually quite happy selling into the emerging markets and actually don't seem that concerned—these guys being the business elite—don't seem to be that concerned that the American market isn't as robust as it could be, 'cause they can make their money through cheap wages in the U.S. and also just the global market. POLLIN: Well, except the global market isn't doing very well either. I mean, Europe is a basket case. Europe is worse than the U.S. So at a certain point we have to have some serious interest in stimulus. I mean, we do have—if you read The Financial Times, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal today, you have a lot of talk about the meetings that are going on at the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, and these elite newspaper outlets are encouraging a stimulus through the central banks, except nobody talks about what the stimulus actually is, what the techniques are, how to do it, how to do it effectively. And so they're stymied, and that in all probability this round of central bank meetings aren't going to be any more successful than all the previous ones. JAY: Right. And as I pointed out when I did my commentary on the G20 documents in Toronto, there's a five-letter word that never gets talked about in any of these meetings, and that is wages. And the idea that wages need to go up as part of a solution you don't hear within the business pages, unless they're talking about China. Then all of a sudden, yeah, the wages should go up. POLLIN: That's true. JAY: Okay. Well, in the next part of our series of interviews with Bob Pollin we're going to kind of wrap up what should be done and talk a little bit more about the politics of all this. So please join us for our summation segment of Bob's new book Back to Full Employment on The Real News Network. [ therealnews.com ] August 23, 2012 A Green Full Employment Economy Requires Mass Mobilization Bob Pollin Pt6: The first steps towards full employment is to create a green engine of jobs growth PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I'm Paul Jay in Baltimore. And we're continuing our discussion with Bob Pollin about his new book, Back to Full Employment. And he joins us again from Amherst, Massachusetts, where he is codirector of the PERI institute. Thanks for joining us, Bob. ROBERT POLLIN, CODIRECTOR, POLITICAL ECONOMY RESEARCH INSTITUTE: I'm glad to be on, Paul. JAY: So we're going to kind of jump to the big picture and what should be done. There's a lot more in the book breaking down many parts of the various arguments. And, you know, we'll give you a link to where you can get the book. But we're going to cut to the strategic vision. And just before we get there, although we heard some of what we're about to hear in President Obama's election campaign in 2008, we didn't see very much of it after 2008, and that was that the engine for driving a transformation of the American economy, both in terms of ending the recession and dealing with global warming and climate-change issues and such, would be to reshape the way American manufacturing works and turn it into an engine of green economy. Obviously the big opportunity for that was the essential nationalization of General Motors. But instead of giving General Motors that kind of mandate, they more or less went back to making cars as they were, but with lower wages, and maybe a little more efficiently, a little bit higher standards on carbon emissions, but not something transformative. So, Bob, in your book, you talk about what should be done and it should be something transformative. And based on our earlier conversations, you're talking about, well, what would—if a government came to power that actually had as an objective full employment, what would they do? And you're kind of laying out what some of those policies would look like. So, then, what does this green economy look like? POLLIN: I think that the stimulus program of 2009 that we've talked about before incorporated a green stimulus feature, a clean energy program that actually could have been transformative. It was orders of magnitude more ambitious than anything that had ever been attempted or even thought about in the U.S. It was on the order of $100 billion to promote energy efficiency, solar energy, wind energy, geothermal energy, public transportation, and so forth. So the roadmap was there. Now, it did not get enacted in the way that I would have liked, even though, full disclosure, I was a consultant on this project, but the basic features of the model are there. And the reason why the green economy is such an outstanding model in terms of moving forward is that, in my view, it combines two things. Number one, obviously, it addresses the problem of climate change. It addresses the issue of having to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions over the next 20 years. The other thing is that in the process of transforming the economy such that it relies much more heavily on efficiency and renewable energy, you also will create millions of jobs. The reason you create millions of jobs is that investing in the green economy is about three times more efficient in terms of creating jobs. It creates three times more jobs per dollar of expenditure than retaining our existing fossil fuel economy structure. Again, that is in the book. The green economy will create about 17 jobs per $1 million of expenditure, the fossil fuel economy about five. So that's—in my view, it's the combination of the two things, that it'll help us solve the climate change crisis and as a result will also be a major engine of job creation. JAY: Now, in the book you talk about some other—you know, they're not so much strategic as short-term fixes, but they lead to a strategic idea of how things might be done, and that is, you talk about canceling a certain amount of mortgage debt. I think it's especially for people whose houses are now worth less than their mortgage. POLLIN: Right. JAY: Some people have suggested canceling student debt, which between those two things would be a major stimulus. So let's talk about those first two. Certainly on the housing side the critique would be that do you then start another housing bubble. POLLIN: Well, the housing bubble was started because we had an unregulated financial market and you had, you know, hundreds of billions of dollars in Wall Street looking for a high return. If you eliminated all household mortgage debt right now, it doesn't mean that you necessarily have to create a new housing bubble. That's why when I talk about industrial policies to advance manufacturing, to advance a green economy, I see those as an alternative engine to relying on another bubble generated by Wall Street. So we could have—we can dramatically reduce debt. That would, of course, effectively put money back in the hands of people to spend, because then they don't have to use it to cover their debts and they can't get out of their houses, they can't move, they can't go look for a job someplace else 'cause they're stuck in their houses because their houses are worth less than their mortgages. We have to clean that up. So that's why in the book I see that as part of the solution for moving us out of the ditch, the recession ditch that we're in. JAY: And part of the argument there, I guess, would be is the banks should do this because they're the ones that created this housing market crash, not the people living in these houses, so why should the people living in these houses bear the burden of something they had no control of. POLLIN: Yeah. And on top of that, the banks were bailed out. And on top of that, the banks can borrow at zero interest rate right now. And on top of that, after they get their free money, they can be redeposit at the Fed with zero risk and earn 0.25 percent just by doing that. So the system obviously is ridiculously rigged on behalf of Wall Street, on behalf of the banks. And, yeah, the political agenda has to be to fight against that. Having a full employment program as a positive alternative is a way to organize a lot of thinking, a lot of goals around something that will be good for people in the short and long run. JAY: Okay. Then let's then get back to the other strategic idea, which is this idea of an industrial policy. And we've talked a bit about this before, but it's worth revisiting, that there in fact is an industrial policy in the United States; it's just that it's being managed by the Pentagon. And what you're saying is there should be some thing similar, except managed by the government—I should say, not by the arms side of the government—and with the objective of employment and ordinary people's well-being. POLLIN: Yeah. Again, if you set as the overarching goal full employment at decent wages and everything that follows from that, you definitely need to incorporate industrial policies to rebuild manufacturing, to advance the green economy. And, yeah, to the argument that says, oh, you know, we're a free market economy, we don't believe in that kind of stuff, it never works, well, the answer is that it does work in the United States, it has worked in the United States. In some cases it's worked spectacularly well through the Pentagon. The Pentagon essentially created the internet through industrial policies, research, development, commercialization, incubation, all of these things that we say the U.S. shouldn't do, can't do, is antithetical to what we believe in the country. That's what created the internet in the first place. And that could certainly, for example, create a solar energy set of technologies that would make solar cost-competitive with traditional conventional energy like coal or nuclear power. JAY: Now, one thing you don't talk about in the book but we've certainly talked about before—but it seems to me it's a big part of this equation on how you could get to a political alignment of forces that would come, you know, get elected, would run governments at federal and other levels. And if they—I would have to think it's a new set of political forces that would take up the kind of policies you're talking about, but in addition to that, the issue of the banking system and who controls it, how it's regulated, but, to some extent, even more who owns it, in the sense that if you don't start challenging that tremendous concentration of political power that comes from concentrated ownership of these enormous banks, that you can't get to these other policies, that somehow you have to have a democratization of the banking sector as a piece of this puzzle. POLLIN: Right. Well, you know, we now have a new recruit supporting that position, which is Sandy Weill, who was the person that created the biggest banking behemoth as a result of deregulation, Citigroup. Just last week he decided that, well, having these gigantic megabanks is actually a bad idea and they need to get broken up. So this is becoming pretty conventional wisdom. Now, what exactly you do about it and how you do it is the huge question. Now you have Sandy Weill, you have other people like that also saying that the Dodd–Frank, the regulatory laws that were passed in 2010, aren't going to be enough. They're too complicated, they're too favorable to business, and so forth. So yeah. Well, it seems to me that, you know, what we really need to do is at least start to think about part of the banking system having a public option, as you have talked about many times, competing with the private banks and serving as a utility. One of the simplest ways to do that is if you just had commercial banks that were effectively utilities, which is what they were under the old regulatory system—they took in deposits, they were very heavily regulated, the deposits are guaranteed, the interest rates that they could charge were limited. And so that at least is a first step in the right direction. But more generally, it's very clear that under the existing financial system, it's going to be extremely difficult to take seriously the kinds of goals I lay out in the book. JAY: So we get back to the political issue, which is there needs to be a different political alignment of forces who runs our governments if we're really going to see policies like this. POLLIN: Yup, absolutely. And that's why, you know, the aim of the book is to mobilize people that actually care about the well-being of working people, unions, people that are supportive of unions, because I think there's no way we're going to move forward unless there is an agenda that is very tied to the well-being of the overwhelming majority of the people that earn their living, that go to work every day, and their interests have to be attended to. I saw in—there was an article in the paper yesterday where Romney is thinking about his slogan being a job for every American. Interesting. So his slogan is kind of the same as my book. Now, how he intends to get there is exactly the opposite. He's saying we need to deregulate even more, we need to give businesses lower taxes, less regulations, less union strength. So, you know, we can have a big debate as to how you get to full employment, and my alternative entails giving workers power, regulating the financial system, fighting for the green economy, and moving forward from there. JAY: Okay. Thanks for joining us, Bob. POLLIN: Thank you. JAY: And thank you for joining us on The Real News Network. [ en.wikipedia.org ] [ en.wikipedia.org ] [ en.wikipedia.org ] [ en.wikipedia.org ] [ okieblog.wordpress.com ] Milton Friedman on Neoliberalism “It Never Occurred to Me That…” « okieprogressive [ mrzine.monthlyreview.org ] Michal Kalecki, "Political Aspects of Full Employment" | |

| » DynV replied on Tue Aug 28, 2012 @ 11:57pm. Posted in Is Full Employment Possible in Capitalism? (1/2). |

this site isn't super as I need to make a 2nd part. :| Your message cannot be more than 50000 characters long [ therealnews.com ] [...] Now, the third great thinker to mention was a contemporary of Keynes named Michal Kalecki. He was a Polish Socialist who was influenced both by Keynes and Marks and had some ideas, obviously, of his own. And what Kalecki said was, okay, Keynes has now shown us how we can utilize the technical apparatus of economic policy to achieve full employment under capitalism, but what Keynes neglects is the change that it would create in terms of political dynamics, that it would give workers more bargaining power, and that the capitalists don't want the workers to have so much bargaining power. It would squeeze profits. Kalecki acknowledges all this. And therefore, he says, though we have the technical tools to achieve full employment under capitalism, we don't have the political force, and it would be a clear challenge to the prerogatives of the rulers of the society, the capitalists, to do this. So he laid out the real tension there. [...] And so the fourth major thinker, most influential thinker, I would say, on the issue of employment is the leading neoliberal economist, Milton Friedman. And Milton Friedman actually said that we have a natural rate of unemployment under capitalism which would be full employment—that is, anybody who wants a job would get a job—if we only didn't have government policies that created barriers to workers and businesses working things out on their own. The example he cited—one of the big examples cited by Friedman is minimum wage laws [...] [...] preview made by me and see my references at the end. Based on: Back to Full Employment  Robert Pollin MIT Press April 2012 4.5 x 7, 112 pp. ISBN-10: 0-262-01757-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-262-01757-2 [ mitpress.mit.edu ] [...] Explaining views on full employment in macroeconomic theory from Marx to Keynes to Friedman, Pollin argues that the policy was abandoned in the United States in the 1970s for the wrong reasons, and he shows how it can be achieved today despite the serious challenges of inflation and globalization. [...] Robert Pollin is Professor of Economics and Codirector of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. [...] [ therealnews.com ] August 15, 2012 The Full Employment Debate Bob Pollin, author of Back to Full Employment, begins a series examining whether full employment is possible and how to get there PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I'm Paul Jay in Baltimore. Bob Pollin, who is a economist and regular contributor to The Real News Network—he's also founder and codirector of the PERI institute in Amherst, Massachusetts—has a new book out called Back to Full Employment. And without further ado, he joins us to discuss this book. Thanks for joining us, Bob. ROBERT POLLIN, CODIRECTOR, ECONOMIC POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE: Very glad to be on, Paul. JAY: Alright. So a lot of people are reading the title Back to Full Employment and they're saying, okay, just when was that? So, obviously, we got to define what you mean by full employment. POLLIN: Full employment is obviously not an obvious thing to define. In fact, in chapter 1 I talk about problems of definition because first of all we have to talk about full employment at decent jobs. You can't think about full employment in any old job, because actually that's very easy to achieve. The worse conditions are, the easier it is to get full employment at lousy jobs or people begging for jobs. So I do discuss that at the beginning, that we're talking about full employment at decent jobs. Now, what do we mean by full employment at decent jobs? Full employment, in my view, a realistic definition is below 4 percent as officially measured by the government. And why is that my threshold? Why below 4 percent? Because what we've seen in the 1960s when we got below 4 percent, and again in the late 1990s when we got below 4 percent, you see a decisive change in the labor market dynamics, such that workers' wages go up pretty significantly, even in the late 1990s. This is after a generation. From the early 1970s to the mid 1990s, the average wage for nonsupervisory workers was either going down or stagnating. When we got the employment rate below 4 percent in the late 1990s due to—the financial bubble at that time was the dot-com stock market bubble—wages went up, especially for people at the lowest end of the labor market. So that's really the immediate goal, I think, about something—a definition of full employment. There's another meaning to the title, and that is that the policy world, the economics profession, needs to get back to thinking about full employment as a policy goal. We're not even there. At least coming out of World War II and through the '60s, the entire edifice of government policy, and for that matter the entire edifice of macroeconomics in the economics profession, was focused around the issues of full employment. Of course, there are different definitions, different policy ideas, but full employment was the central idea. We've completely abandoned that. JAY: Well, the idea of full employment—and in your book, in one of the later chapters, you kind of dig into this more—but capitalists have always understood—and, I guess, so have socialists—that high unemployment is good for capitalists, to a certain extent, at least, 'cause it dampens wages. And this, you know, polarity between wages and profits and this dynamic has always meant there needs to be a certain level of unemployment. And I think Milton Friedman—I don't know if he coined the term or not, this idea of a natural level of unemployment, that they want to control wages, and so they will almost turn a tap one way or the other so that full employment really isn't their objective, even though legislatively on paper, like the Full Employment Act of 1946, they say it is. But is it really? POLLIN: No, of course it isn't. Full employment is definitely a challenge to the dynamics of a labor market under capitalism, precisely as I was saying before, because it gives workers more bargaining power. The idea goes all the way back to Karl Marx. The idea goes back to Marx's notion of—his term was the reserve army of labor, which is the reserve army of unemployed people. When you have a lot of unemployed people, then if the people that are employed try to bargain up their wages or improve the conditions, the owners can just say, well, if you don't like it, you know, I'll just hire those people that don't have a job; they'd love to have your job. There's a lot of truth in that. So that is the basic dynamic that Marx described. And Marx himself said, therefore capitalism by its nature requires mass unemployment, requires a reserve army of labor. And we can debate, but I think one of the fundamental critiques that Marx had of capitalism was exactly on this point, that you couldn't really build a decent society under capitalism, because in order for it to function on behalf of capitalists, you couldn't have full employment. So when I say a full employment economy, definitely I am talking about changing the dynamics of the economy, about challenging the prerogatives of capitalists, and doing it in a systematic way. So that's really the nature of the debate around how to get to full employment within the basic structure, still, of a private ownership market economy. JAY: So part of your thesis is that there have been moments in American history, you know, modern American history, where you have seen low unemployment. Some of that had to do with public policy. And when you say "back to," you're partly talking about going back to that, as you say, still within the capitalist system. Is that correct? And then, if that's true, when are those moments? And give us a bit of that history. POLLIN: The two periods in the post-World War II era in the United States where you had something close to full employment—so that is, again, below 4 percent—were the late 1960s and the late 1990s, and both experiences are instructive. In the late 1960s you did have a deliberate policy effort to stimulate the economy through macroeconomics, through a tax cut that was started by President Kennedy, continued by President Johnson. At the same time, under Johnson you had very aggressive policies, relative to what we've had subsequently, in terms of giving an opportunity for people at the low end of the labor market. So that pushed the economy down to below 4 percent unemployment. And you did see very significant gains in terms of poverty reduction, in terms of decent wages, of wages going up, especially for low-income households. So that's exactly why I'm looking to full employment to achieve that again. Now, you had roughly the same outcomes in the 1990s when—and this was largely as a result of the financial bubble of the 1990s, which drove a very rapid increase in both private spending, consumption spending, and investment spending. It was a bubble and therefore didn't last, but for a brief period the unemployment rate officially fell below 4 percent. And yet again you saw wages went up very rapidly, especially for people at the low end, poverty was reduced, and workers did increase their bargaining power. So these are very, very important achievements, and they can be attained within a framework of the existing capitalist economy we have now. JAY: It could be if they wanted to. The question is: those that have power, you know, do they want to? Like, go back to this Humphrey–Hawkings Act, where they take the Full Employment Act, which was—what, 1946 was it? POLLIN: Yeah. JAY: And then they change the objectives. It's not just now there should be a maximum unemployment rate of 4 percent, but now they also have inflation objectives. POLLIN: Right. JAY: And I think you told to me off-camera it's like really watering down the 1946 act. And this was Hubert Humphrey the great Democrat. And this starts to make the actual policy objective—they say inflation, but we know that's code for let's make sure wages don't get too high. POLLIN: Right. What happened in the 1970s was that you did start to get higher rates of inflation. The reason you got higher rates of inflation was the oil price increase. In 1973 you had a 400 percent increase in oil prices, and then you had it again in 1979. So that set off this inflationary spiral. The source of the inflation was not workers' bargaining power. You did get some increase in inflation due to workers having more bargaining power in the late 1960s, but that was not by any means the primary cause of the inflation of the 1970s. So in the book I do talk about the issues of how to control inflation. And there does have to be some concern about inflation control. I don't deny that. What we do need to do, though, is not what—where we've gotten, essentially, now in macroeconomics analysis and policy is really to say, well, look, we can't really do anything about employment through government policy. We can control inflation, so let's just stick with inflation and let job creation land wherever it lands. That's what we got out of, like, 30 years of macroeconomics, which then brought us to the Great Recession, such that orthodox economists, when the Great Recession started, had almost nothing worthwhile to say, because they'd been focused entirely on this issue of inflation control. JAY: So in the next segment of our interview, we're going to pursue this discussion, and the question is actually the question Bob raises in chapter 2 of his book, which is: is full employment under capitalism possible? So please join us for the next segment of our series of interviews with Bob Pollin on The Real News Network. [ therealnews.com ] August 16, 2012 Is Full Employment Possible in Capitalism? Bob Pollin Pt2: There have been periods of unemployment less than 4%, those conditions could be created if there was intent to do so PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I'm Paul Jay in Baltimore. We're continuing our series of interviews with Bob Pollin about his new book, Back to Full Employment. And he joins us again from Amherst, Massachusetts, where he is codirector and founder of the PERI institute. Thanks for joining us again, Bob. ROBERT POLLIN, COFOUNDER, POLITICAL ECONOMY RESEARCH INSTITUE: Thank you very much, Paul, for having me again. JAY: So if you haven't watched part one, go watch part one. Part two, the question is: is full employment under capitalism possible? So, Bob, some people would suggest the answer to that question is: if full employment under capitalism was possible, they wouldn't be capitalists. In other words, if they did implement the kind of policies you're talking about, it would just go against their nature. And so how do you answer that? POLLIN: We have evidence that full employment has operated under capitalism. It certainly operated, as we talked about in the last segment, briefly in the United States in the late '60s and late '90s. It certainly operated in Europe in the early period after World War II. We have a lot of evidence, for example, in the Nordic countries. Sweden is a really good example of—because the unions in Sweden had a lot of political power, they were able to do some very interesting experiments to push the economy toward full employment and stay there. The unions had enough power that they could think about macroeconomic policies to push the economy to full employment, while the unions themselves were focused as well on inflation control, restraining inflationary pressures, so that you could actually sustain the full employment that would be good for workers over time. And so we do have experience that this has happened. It is a different kind of capitalism. It is a capitalism in which workers have more power, unions have more strength, the concern for the well-being of working people is much higher than it is today. And that's the kind of society I think we need to move toward. Where we go after that, okay, we can talk about where we go after that, but just to get to that point in which public policy is genuinely focused on providing a maximum amount of job opportunities and well-being for people, to get to that point in our policy debates would be a major achievement. JAY: And we'll get into that, how you think we get there, a little further in this series of interviews. But let's kind of go step by step here. So give us—trace us a little bit about the history of this debate. As you said in part one, Marx says it's in the interest of capitalists to have a certain level of unemployment because it controls wages, and then Keynes kinds of counters that argument to some extent in terms of the role government could play. So give us a bit of the historical background here. POLLIN: Alright. Well, I go through what I think are the four major thinkers on the theory of unemployment. The first is Marx, and it was Marx who said that having a reserve army of labor, a lot of unemployed people, is necessary for the functioning of capitalism, because if you had no unemployment, then workers' bargaining power would go up, workers' wages would go up, capitalists' profits would get squeezed. Okay, that's Marx. Now, Keynes came in with a different view. Keynes was thinking more as a technician within the framework of capitalism. And he said, if you do not get to full employment through private investment in the economy, then the government should step in and engage in public investment. His term, Keynes's own term, was "somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment". And if the government did this somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment geared towards creating maximum job opportunities, that would be a better society, a different kind of capitalism. But technically, he said, it could be done. Moreover, the central Keynes point was that actually this could be good for capitalists as well, because even though workers would have more bargaining power, you would also have the economy expanding more rapidly, the markets would be more buoyant, there'd be more opportunity for new business investment, just because workers would have money in their pockets and they could buy things, just like Henry Ford was famous in recognizing that if you paid workers decent wages, well, then workers might actually be able to afford to buy Ford automobiles. JAY: Right. And this Keynesian idea's heavily influenced this act that we talked about earlier, the Humphrey Hawkins Act, 'cause if I understand correctly, in that act it actually says if the private sector can't create enough jobs to get unemployment at 4 percent, then the government should use public works to do it. I mean, it was in the legislation; I don't think it was ever really enacted, 'cause five years later, unemployment's at almost 10 percent. But the ideas were very influential. POLLIN: Right. So you have Marx and Keynes, and those are also reflective of different notions about how capitalist economy functions. Keynes was much more in the social democratic tradition, operating within the institutions of capitalism. Now, the third great thinker to mention was a contemporary of Keynes named Michal Kalecki. He was a Polish Socialist who was influenced both by Keynes and Marks and had some ideas, obviously, of his own. And what Kalecki said was, okay, Keynes has now shown us how we can utilize the technical apparatus of economic policy to achieve full employment under capitalism, but what Keynes neglects is the change that it would create in terms of political dynamics, that it would give workers more bargaining power, and that the capitalists don't want the workers to have so much bargaining power. It would squeeze profits. Kalecki acknowledges all this. And therefore, he says, though we have the technical tools to achieve full employment under capitalism, we don't have the political force, and it would be a clear challenge to the prerogatives of the rulers of the society, the capitalists, to do this. So he laid out the real tension there. But within Kalecki there is still the point that if you get a bigger market, then capitalists can benefit from a more buoyant market, even if the wages are higher and the capitalists' share of the total market, the income coming back to them, is lower because workers have more bargaining power. That's the tension. And so the fourth major thinker, most influential thinker, I would say, on the issue of employment is the leading neoliberal economist, Milton Friedman. And Milton Friedman actually said that we have a natural rate of unemployment under capitalism which would be full employment—that is, anybody who wants a job would get a job—if we only didn't have government policies that created barriers to workers and businesses working things out on their own. The example he cited—one of the big examples cited by Friedman is minimum wage laws, because he said—and unions. Unions, minimum wage laws get in the middle between the workers and the owners. The workers and the owners keep bargaining till they got a wage that everyone can agree to, and then you would have full employment. You just don't want to have these institutional forces like minimum wage laws, like unions, telling the bosses that they have to pay workers more than the workers deserve. So that kind of sets the whole scene of the debate. Unfortunately, the winner of the debate over the last generation, not just in the U.S., throughout the world, was clearly Milton Friedman, and so that what we have under neoliberalism for essentially the last 40 years is an abandonment of any attempt by government policy to sustain full employment, to use government policy to soak up people that are having a difficulty getting jobs and creating job opportunities for them. JAY: You can almost say the objective of government policy was the opposite, was to make sure that unemployment never fell below a certain level, because that would, they would say, instigate inflation, their code word for higher wages. So if anything, government policy was the opposite. They wanted what—quote-unquote, this natural level of unemployment. POLLIN: Right. Well, that's certainly—you know, Milton Friedman was certainly the leading figure in advancing this view in the economics profession, and it spilled into policymaking. And the view was, right, actually, the government is incapable of achieving full employment anywmay; in fact, government is a barrier by, for example, setting up minimum wage laws; but that the government can do one thing, and that is to control the inflation rate, and so that's what macroeconomic policy should be focused on. Now, it turns out the way you control the inflation rate is by keeping the unemployment rate higher, because, precisely, if the workers get too much bargaining power, then that enables them to push up their wages. That then means that businesses will try to pass on those wage increases in terms of price increases to consumers. And that's how you get inflation. So you have this notion of the tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. JAY: But that tradeoff is, you know, if you look at the period we're talking about, essentially from 1960 forward, the big spikes in inflation didn't have anything to do with high unemployment. Like, the biggest periods of inflation were actually periods of, also, high unemployment. POLLIN: Right. And that was—as we talked about in the last segment, that was due to the oil price shock. So the initial theory of the tradeoff between inflation and unemployment completely ignored the fact that there could be other majors sources of inflation. It was very convenient, by the way, because, okay, you get an oil shock, inflation goes up, you have a recession, and then the Friedmanites of the economics profession say, a-ha, there is no tradeoff; in fact, what we see is government efforts to reduce unemployment are just making inflation worse and aren't reducing unemployment anyway; so let's abandon the whole thing; the whole Keynesian thing was wrong. And that's how we got the macroeconomics that we have now, which brought us to the Great Recession. JAY: So in the next segment of our interview, we're going to pursue this discussion. So please join us for the next segment of our series of interviews with Bob Pollin on The Real News Network. [ therealnews.com ] August 17, 2012 Full Employment and the Swedish Model Bob Pollin Pt3: In the quest for a short term solution to the crisis, there is a lot to learn from Swedish social-democracy PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I'm Paul Jay in Baltimore. We're continuing our series of interviews with Bob Pollin about his new book, Back to Full Employment. And he joins us again from Amherst, Massachusetts, where he is codirector and founder of the PERI institute. Thanks for joining us again, Bob. ROBERT POLLIN, COFOUNDER, POLITICAL ECONOMY RESEARCH INSTITUE: Thank you very much, Paul, for having me again. JAY: So in terms of modern history, one of the models that's often pointed to, at a country that kind of tried to marry Keynesianism and that form of capitalism that seemed to have been working to some extent, was in Sweden. And you talk about this in your book. So discuss that model a bit. POLLIN: Well, I think that's a very, very rich model with a lot of lessons for countries throughout the world. I myself, in work I did several years ago in Kenya, actually, on employment opportunities in Kenya, was thinking about the Swedish model in writing the book on Kenya—and still thinking about it in a book about the United States. So it isn't so much about Sweden, per se. The idea is that, okay, we have the Keynesian tools that can promote employment. We do know that at a certain point you will create inflationary pressures, and so that how do you maintain a full-employment economy that benefits workers. And the best way to do it is when you have strong unions that are committed to full employment. And they will maintain wage increases that are roughly consonant with productivity growth, so that you do not get upward price pressure, because every time you get a wage increase, that's roughly in step with the economy's capacity to produce more goods and services. That's a productivity increase. And it was really due to the unions themselves that attempted and implemented this policy. In fact, the innovators here were two outstanding union economists, Rudolf Meidner and [?g?st?'r??n]. (I don't know how to pronounce the names correctly. I'm sure I'm mangling them.) But they were very important economists in thinking about how to achieve and sustain a full-employment economy, precisely by empowering workers. Empowering workers gives workers the sense of responsibility [inaud.] oh, well, we are going to take responsibility for dampening whatever inflationary pressures may result, and yes, we can sustain a little bit higher rate of inflation, but we will make sure that prices and wages do not go up excessively, precisely because we the workers, we the unions have the power to do it. So I think that is a very rich model. They were able to maintain unemployment for 20 years or more at around 2 percent, and the inflation rate was basically stable, even though you had oil price shocks in Sweden as well. JAY: But but over time, the neoliberal pressure took over Sweden as well and the power of finance asserted itself, and they started undoing that model. POLLIN: That's right. Well, the Swedish model is still a lot better than the U.S. model [crosstalk] JAY: Well, everything's better than the U.S. model. POLLIN: —yeah—and the rest of Europe. So Sweden still stands out as a very—as a country that's performing much better, has much lower levels of inequality. But, yes, a lot of the model has been cut back. But we have to have something to grab on to when we think about how to build out and come up with alternatives out of the Great Recession and the disaster that neoliberalism has inflicted both in the United States and the rest of the world, and I think there's a lot to learn from the Swedish model. I don't say it's perfect, but I think if we think about policies of moving from where we are today, not just thinking about a utopian alternative that we can envision, but policies starting with where the world is today, in the neoliberal swamp, I say that the Swedish model has a lot to offer for moving us forward. JAY: Okay. We're going to pick up this discussion about the Swedish model and such a little further in the series, 'cause we're going to come back to, keep revisiting many of these issues. But we're going to—in the next part of this series of interviews, we're going to pick up on the next chapter of Bob's book, which is "Globalization, Immigration, and Trade". And part of one of the ideas Bob raises is this idea of the reserve army of the unemployed actually becomes the whole world, and global workers and low-paid workers and global unemployed workers used as a lever against North American and European workers. So we'll pick that up in the next part of our series with Bob Pollin on The Real News Network. [ therealnews.com ] August 19, 2012 Is Full Employment Possible in the Era of Globalization? Bob Pollin Pt4: The global "army of the unemployed" weakened American labor, but tariffs are not a solution - a mass mobilization is needed PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I'm Paul Jay in Baltimore. We're continuing our series about Bob Pollin's new book, Back to Full Employment. Now joining us to continue this discussion is Bob Pollin. He is the founder, codirector of the PERI institute in Amherst, Massachusetts. Thanks for joining us again, Bob. ROBERT POLLIN, CODIRECTOR, POLITICAL ECONOMY RESEARCH INSTITUTE: Very glad to be here. Thank you, Paul. JAY: So just to pick up our last conversation, if you haven't watched the first few parts of this series, I suggest you watch it in order, 'cause all this conversation will make more sense that way. We were talking about your chapter in your book "Is Full Employment Possible under Capitalism". And part of the idea or concept of the book is that there used to be a full-employment objective in public policy in the United States. And I think probably one of the main markers for that is 1946 with the Full Employment Act. But some people would argue 1946 is a very specific kind of year. First of all, you have more workers on strike in 1946 in entire American history, if I understand correctly. Before '46 and after '46 there were, I have, 4,985 strikes, 4.6 million workers on strike, for a total of 116 million strike days. So in the context of that—and there was—many, many of the soldiers coming back were unemployed. Plus you had the Soviet Union, which at least for many workers held out the promise of a socialist system that was going to work. And one of the most important things about this socialist system, people thought (and we know this promise was not fulfilled, but still, in '46 a lot of people thought it would be), was full employment. So within the context of the beginnings of the Cold War and all these strike struggles, you get the Full Employment Act. But some people would argue, you know, now the socialist models of Russia and China have failed, and then, particularly with globalization, the ability—as we've talked about a little bit in the earlier segment of the interviews, the ability for capital to use this global reserve force of unemployed or very cheap labor as leverage against the American workers, that they no longer need to make these kind of compromises like they did in '46, or even the New Deal in the '30s, that they can be far more—what's the word?—intense in how they go after American workers, and that full employment simply isn't their objective, so that the set of policies you're talking about or the toolkit you're talking about might well work, but these guys won't do it—. What do you make of that? POLLIN: Well, the objective of the book was to lay out what I tried to show was a feasible path to full employment, to show how it can be done within the confines of a broadly capitalist system today, so that we can energize political forces today—today—to fight for decent jobs for anybody that wants a job today. Now, the political forces, that is another issue. In fact, the whole point of the book is to help mobilize political forces. Of course I know full well that the political forces are very different today than they were in 1946, and for that matter in the 1970s. But we also have a crisis on our hands. We had a crisis that started due to the collapse on Wall Street in 2008 and 2009. Employment conditions remain worse than at any time since the Great Depression. So it seems like an appropriate time to start thinking about ways through which we can fight for decent livelihoods and full employment for people in this country. Of course it's going to take a political mobilization to get there. I mean, we did have—for example, last fall we had the Occupy Wall Street movement, which created a lot of tremendous energy around social justice and workers' rights and inequality in the country. Now, the Occupy Wall Street movement did not attach itself to any specific set of policies—on purpose. They deliberately chose not to. But I would say when we have a second round of this kind of movement, that it should indeed focus on some specific policies, and top on the list, in my view, should be full employment. And it's because full employment is not just about jobs. Of course it is about jobs, but it's about decent jobs, it's about inequality, it's about reducing poverty. And in order to have any chance of getting to full employment, you also have to to have a highly regulated, stable financial market. JAY: Okay. Well, when we get to the final segment, we'll kind of explore some of the big ideas again. But let's kind of dig into one piece of this, and that is the whole issue of globalization, because certainly, you know, in the postwar years, one—the fall of the Soviet Union is one major factor on the political, you could say, ideological side of this question. But on the sort of objective economic balance of power between business and workers, the biggest development, I would guess, is this globalization of labor, where now you can produce at a very sophisticated level in markets that have high—in countries that have enormous unemployment, very low wages, and bring the products back to the U.S. So talk about the effect of globalization and then what this means in terms of full employment. POLLIN: Well, globalization, the impact of that on the U.S. labor market—and we can talk about it in other countries as well, but the impact on the U.S. labor market has been going on since the 1970s increasingly. And the single clearest indicator of the impact of this formation of a global reserve army of labor, that is, that businesses can threaten workers in the U.S. by saying, well, we're just going to go produce in China and workers are going to get one-twentieth of what you get—so that seems to me the biggest single factor with globalization, the credible threat that U.S. businesses can use against workers in this country. The impact has been two generations of wage stagnation. The average worker in the United States today is earning about 7 or 8 percent below what the average worker earned in 1973. JAY: Yeah, you give the numbers in your book. You have $19.47 an hour in 2011 dollars for the average nonsupervisory worker today, and in 1972 the same worker would actually be making, as you said, 7 to 8 percent more, $20.99. POLLIN: Right. And the other part of that figure that I show is that that stagnation or decline in the average wages occurred while average productivity in the U.S. economy, that is, the amount that the average worker produces over the course of a day or over the course of a year, has doubled. So the average worker coming to work is producing twice as much as they did, roughly, in 1970, in the early '70s, whereas they're getting paid about 8 or 9 percent less than they did. There's really never been this kind of pattern before that I know of in U.S. history or in the history of any advanced capitalist country. So the workers have been really getting clobbered by globalization. Now, that is one of the main themes of the book: how do you fight against that? That is one of the questions that I try to raise in the book, counteracting those pressures from globalization. JAY: Let's go there. I know if we'd follow directly chronologically in the book, this isn't the next thing you take up, but you have in previous interviews. For example, you deal with is immigration or illegal immigration really a problem. We've done interviews about that. You can watch it below us. We've done interviews on—. But let's pick up on what one solution to globalization is, and maybe then go to what you think it should be, and that's the issue of trade tariffs, that some people are saying there should simply be a return to tariffs on imported goods, protect the American market, and in that way protect jobs for American workers, and you hear that both from the right and sections of the left. POLLIN: Right. Right. Now, the issue that I raise in the book—it was really two sets of issues. One, is this the kind of policy that really has a big chance of success? My view is that the chances of success are not very good. JAY: "This policy" meaning protectionism. POLLIN: The policy of trade protectionism as a counterforce to globalization. And the basic reason why I don't think it's going to succeed is, if we think about the policy tools that we have, they're basically ways to set up barriers so that, say, Chinese goods are more expensive. And the most basic way to do that is to force the Chinese to raise the value of its currency, the yuan, relative to the dollar, or, correspondingly, for the U.S. to push down the value of the dollar relative to the yuan. Whether we can even do that if we try is itself questionable. I mean, the U.S. right now—the Fed is trying to decide what to do to try to move the growth in the U.S. economy forward. And the measures that we've taken have had only limited success. There's no reason to assume that the U.S. would be capable of moving the dollar to where it wanted to be relative to China even if it wanted to. In addition, why wouldn't China or any other developing country that depends on the U.S. market retaliate? They will retaliate. JAY: In other words, you start getting currency wars and everybody tries to keep dropping below the U.S. dollar wherever it goes. POLLIN: That's right. And then the other thing is, even if at the level of national governments Third World countries didn't retaliate, the producers in the Third World, they will retaliate. They don't want to lose the U.S. market. So what they will do is push down the wages of the workers in the Third World. So that'll force super exploitation on the workers that are already getting paid too little. So I don't really see this as a viable solution even technically, certainly not in terms of solidarity. And the other issue in terms of solidarity is I don't think that the U.S. should be focused—certainly progressives in the U.S.—should be focused on creating jobs for U.S. workers by taking away jobs from Third World workers. JAY: You could add another piece to that too, which, if the history of the 20th century's to be understood, and before that, you know, trade wars, which essentially a currency war would be, and especially if you add protectionism to that, tend to lead to real wars. POLLIN: Right. So I don't think, for all of these reasons, that is a viable policy. Around the edges, of course, you know, we can negotiate with China and talk tough and all that, and I do favor industrial policies to promote manufacturing and the green economy in the U.S., but I don't see that as, necessarily, an aggressive trade policy against Third World producers. JAY: Okay. So let's go. In the next segment, we're going to go to—then let's look at what would be viable policies. And we'll start looking at—both in terms of—and we're going to start with an assessment of did the Obama stimulus work, and if it didn't, why didn't it. And then we'll go from there. So thanks very much for joining us on The Real News Network, and join us for the next part of our series with Bob Pollin. | |

| » DynV replied on Mon Aug 27, 2012 @ 9:39pm. Posted in arrrgh. |

I hate that "new dubstep" or "some EDM with *very* vague reference to dub" grinding sound. what's the name of it? it has become the flavor of the year like autotune ; you hear it in other genres.  | |

| » DynV replied on Mon Aug 27, 2012 @ 1:50am. Posted in What are you listening to right now?. |

John B Feat. Shaz Sparks - Shining In The Dark (Extended Mix) | |

| » DynV replied on Fri Aug 24, 2012 @ 12:30pm. Posted in Sept. 4 elections. |

la CAQ est juste une marionnette des libéraux tant qu'à moi. à genoux "oh! dis-moi c'que j'dois faire pour revenir au bercail." | |

| » DynV replied on Fri Aug 24, 2012 @ 1:07am. Posted in Sept. 4 elections. |

I say liberals are re-elected. remember: old people vote, they decide. | |

| » DynV replied on Thu Aug 23, 2012 @ 7:14am. Posted in 2012 Rave.ca Troll Awards. |

[ bitchinnravin.ca ] ? | |

| » DynV replied on Wed Aug 22, 2012 @ 9:35pm. Posted in 2012 biggest faggot on rave.ca award. |

un TDC talentueux  | |

| » DynV replied on Wed Aug 22, 2012 @ 9:28pm. Posted in 2012 biggest faggot on rave.ca award. |

Originally Posted By TOY_POLICE Where you hear Bliss on a regular basis Bar Chez Roger Tous Les Mardis 6 to 1 am L"Assommoir Tous les deux Vendredis 7 to 1am c'est pas de quoi se vanter mais y'est quand même payé régulièrement. j'me demande le % de DJ avec un peu de talent qui réussissent ça. | |

| » DynV replied on Wed Aug 22, 2012 @ 5:51pm. Posted in keept at it. |

DynV's Profile - Community Messages | [ Cumbre de Página ] |